-

Setup pre-arm in betaflight

I have recently taken up FPV drone flying. It is both difficult and satisfying. /r/fpv has been a helpful community in getting started and finding great gear that works well together. One thing I came across was a recommendation to enable pre-arm on your drones, but it took some research to figure it all out as a beginner.

Setting up pre-arm means you need both hands engaged to arm your drone before flight. This can protect you from accidental arming a drone and getting cut on the propellers. Common stories include locating a downed drone and picking it up, the radio dangling on its leash and the arm button is bumped. Graphic pain follows.

Steps to setup pre-arm

The setup is easy and straight forward once you know how. It is directly supported in betaflight, so it will merely take a few minutes to configure and no advanced steps necessary.

Start out by considering what button on your radio you want to use for pre-arming. I picked a momentary switch (one that outomatically switches to OFF after clicking it) on the opposite side of the radio from the ARM toggle, just to make sure I need to use both hands to arm the drone.

- Using Chrome on your computer, open the betaflight web version at app.betaflight.com. This is easier than installing betaflight natively on your machine. As of the time of writing, only Chrome supports communicating with USB peripherals.

- Connect to your drone with USB or bluetooth.

- Click

Modesmenu on the left. - Power on your Radio and connect it to the drone (your remote controller).

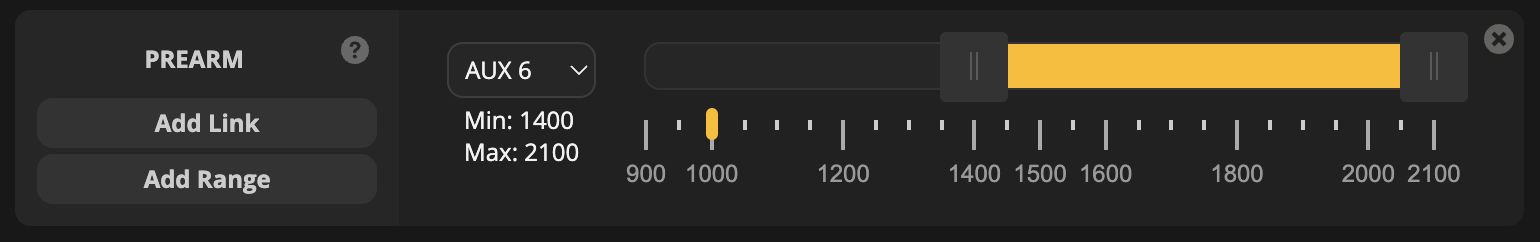

- Find “PREARM” in the list of modes in betaflight.

- Click “Add Range”, pick “AUTO” as the input in the dropdown.

- Toggle the switch on the radio you want to serve as your pre-arm switch. In this setup I use the momentary switch

SFon the RadioMasterBoxer. The “AUTO” will now automatically switch to the actual button identity. Turns out this isAUX6for this particular radio. See what the on/off outputs of your button are, and adjust the range to match by moving the sliders. I only want “pre-arm” to be true when the button is held.

See what the on/off outputs of your button are, and adjust the range to match by moving the sliders. I only want “pre-arm” to be true when the button is held.

Once you think everything is setup right, click your chosen botton on/off a few times, and see if PREARM lights up when you expect it to. Click “Save” and you’re done!

Pre-arming before flying

- Hold the

SFmomentary button. - Then arm the drone by switching the default

SAswitchON. - Drone is now armed and ready to fly.

- Disarming: switch

SAtoOFFand the drone immediately switches off.

Other options

The above is a setting within the specific drone. If you have multiple drones you want to behave the same, you could also configure a logical pre-arm sequence in your Radio.

-

Spelunking an ActionCable Error

Upgraded an app to Rails 5.0.7, and after following the official migrations steps, the app completely failed to load.

The exception itself was rather puzzling:

undefined method 'logger' for nil:NilClass (NoMethodError), raised deep inside of ActionCable atlib/action_cable/engine.rb:20:initializer "action_cable.logger" do ActiveSupport.on_load(:action_cable) { self.logger ||= ::Rails.logger } endSo, how can this seemingly simple code go wrong? Let’s read backward from what is calling the above

on_loadcode-block.According to the documentation for

ActiveSupport::LazyLoadHooks, the code added toon_load(:action_cable)is triggered whenrun_load_hooks(:action_cable, context)is called at a later time, with a context object passed in. In this case, thecontextpassed toon_loadwas unexpected anilvalue.Let’s look closer to what is actually passed to this

run_load_hookscall:ActiveSupport.run_load_hooks(:action_cable, Base.config)Let’s check the

ActionCable::Server::Base.configmethod definition:cattr_accessor(:config, instance_accessor: true) { ActionCable::Server::Configuration.new }The intent here is the

Base.configmethod lazy-initializes anActionCable::Server::Configurationinstance and re-uses that for subsequent calls.Somehow that initialization fails to run in our case, and we get

nilvalue returned instead.Inspecting the weirdness

So, here’s how I finally figured out what was going wrong, with the above code reading context in mind: I used

bundle open actioncableand edited the end of thelib/action_cable/server/base.rbfile locally like so:require 'pry'; binding.pry # <-- ADDED THIS LINE ActiveSupport.run_load_hooks(:action_cable, Base.config) endI added

gem 'pry-rails'to the projectGemfile, and started a Rails console.Time to show where the

Base.configmethod is actually defined:[1] pry(ActionCable::Server)> show-method Base.config From: ~/.rbenv/versions/2.5.1/lib/ruby/gems/2.5.0/gems/table_print-1.1.4/lib/table_print/cattr.rb @ line 9: Owner: #<Class:ActionCable::Server::Base> Visibility: public Number of lines: 1Surprise! Hello

table_print-1.1.4, didn’t expect to see you here. That most likely explains why the lazy initialization was skipped, an old monkey-patch gumming up the works.Removing

table_printfrom the projectGemfile, and re-running the console, we get:[1] pry(ActionCable::Server)> show-method Base.config From: ~/.rbenv/versions/2.5.1/lib/ruby/gems/2.5.0/gems/activesupport-5.0.7/lib/active_support/core_ext/module/attribute_accessors.rb @ line 60: Owner: #<Class:ActionCable::Server::Base> Visibility: public Number of lines: 3 def self.#{sym} @@#{sym} endWith the removal of the old gem, the Rails app succeeds in booting the Rails console. There was much rejoicing.

As we’re done debugging here, let’s clean up the edited

actioncablegem:$ gem pristine actioncable Restoring gems to pristine condition... Restored actioncable-5.0.7A conclusion of sorts

Reading, understanding and messing with the Rails source are sometimes the only way forward when things behave unexpectedly.

binding.pryis a good friend andshow-methodcan really save the day, especially when the observed behavior doesn’t match the source-code.Got any weird puzzling bugs holding your project back? I’d be happy to take a look. Contact details below.

subscribe via RSS